The Liber Floridus

The most famous masterpiece in the collection is, of course, the Liber Floridus.

This manuscript has been in Ghent since the 13th century. The author of this medieval century encyclopaedia is Lambert of Saint-Omer, a canon at the Church of Our Lady in Saint-Omer. The last additions to Lambert's manuscript date from 1121. Saint-Omer was one of the leading economic and cultural centres of the Earldom of Flanders in the 12th century. A crucial fact since Lambert's Liber Floridus, as an encyclopaedia, is above all a compilation of extracts from other books he had access to in Saint-Omer. Thus Lambert extensively uses and copies the much older and then leading encyclopaedias of Isidorus of Seville, Beda Venerabilis and Rabanus Maurus, but equally nearly a hundred other sources. In turn, Lambert's work was copied several times, as evidenced by the many preserved later copies.

Liber Floridus BHSL.HS.0092

Who was Lambertus?

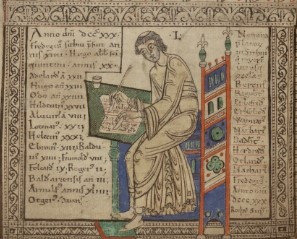

Relatively little is known about the author of the Liber Floridus. We cannot derive much information from his name Lambertus, as the name was anything but exceptional at the time. He does mention his father Onulphus who, like himself, was a canon at the Church of Our Lady in Saint-Omer. Onulphus died in 1077, of Lambert we know neither birth nor death date. We suspect that he finished the Liber Floridus around 1121. At the very end of the Liber Floridus is a genealogy of the ancestors on his mother's side. This goes back to Lambertus' great-great-grandfather Odwin. Finally, he inserts a self-portrait, placing himself in a long tradition where the author is depicted writing on his work at the beginning of the book.

A medieval encyclopeadia...

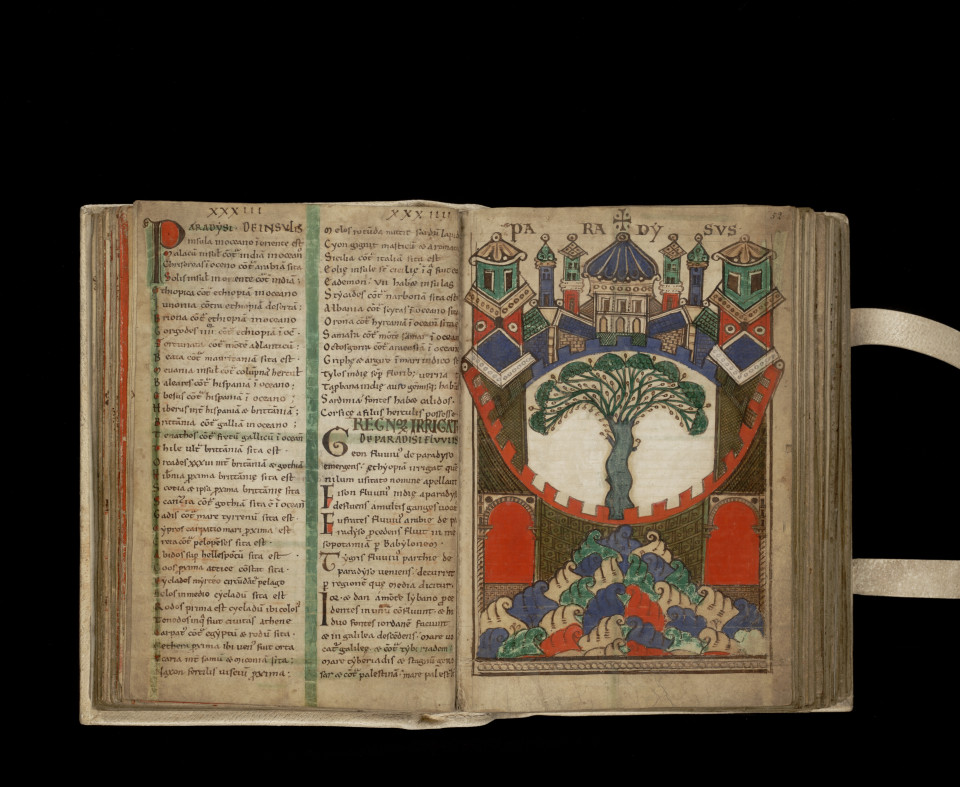

The Liber Floridus is a medieval encyclopaedia where content was seemingly not organised in any way, but the chapters sometimes follow each other in random order, with the intention of counteracting loss of ‘knowledge’. The encyclopaedia has an organic structure, with knowledge embedded in the worldview. Lambert noted 161 chapters in his table of contents. They are often mere lists of names of popes, peoples, kings, inventors, provinces, founders of cities, genealogies and the glorious deeds of the Counts of Flanders and many other princes. eschatology (the doctrine of last things) is never far away and at the end of time a new and heavenly Jerusalem beckons.

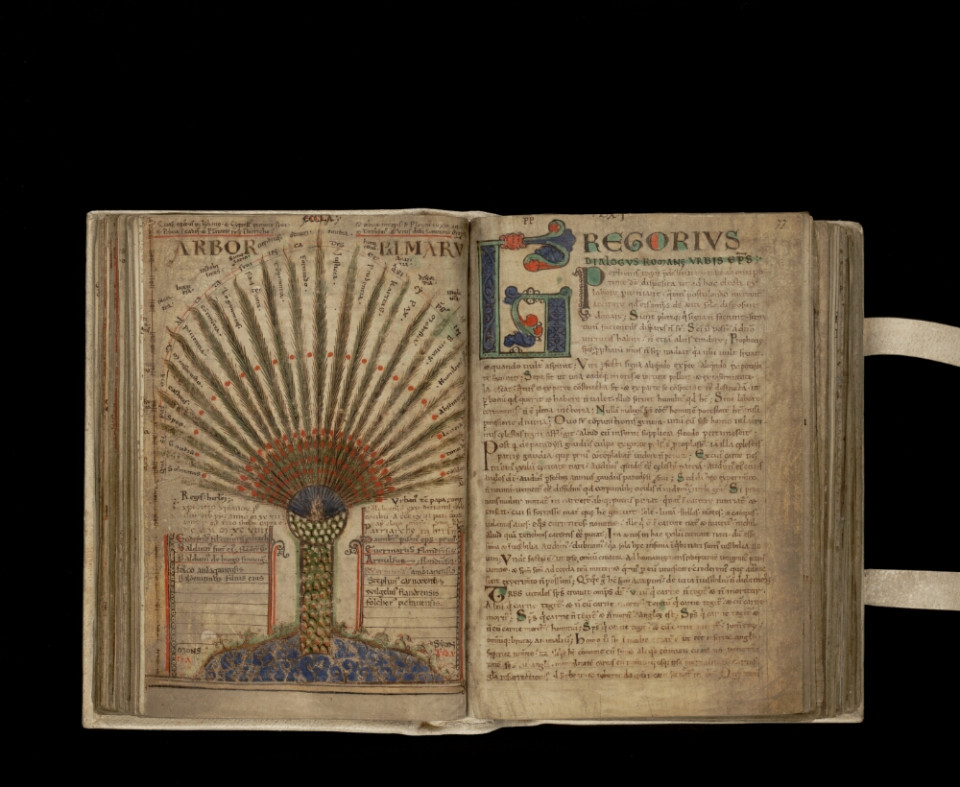

This beautifully self-written manuscript is unique in any case, but it is also perhaps the oldest richly illustrated encyclopaedia. Not only does Lambert place himself in a long tradition by depicting himself writing at the beginning of the manuscript, but some of the images are commonly considered masterpieces of Romanesque art. A very typical example is the trees of virtues and vices. This beautiful artwork covers two pages with the roots of the trees touching in the fold of the book. Morality and natural history are captured in one image. The different branches of the tree of virtues bear different leaves representing a specific virtue, and female figures in the respective medallions. The colourful tree is directly identified with the Church of the Faithful. Diametrically opposed to this flowering tree is the barren tree of vices. No female representations in the medallions, just a textual representation of the various sins. Just as the virtues are identified with the Church, so Lambert's anti-Semitism is expressed in the identification of the barren fig tree with the Synagogue.

...in Ghent

Since the 13th century, the autograph of the Liber Floridus has been kept in Ghent: first in St Bavo's Abbey, later in St Bavo's Cathedral. This should come as no surprise. There were quite a few exchanges between Saint-Omer and the Flemish cities. After the French Revolution, the manuscript was confiscated and included in the collection of the Ghent City Library. Shortly after the foundation of Ghent University in 1817, it was given in long lease to Ghent University along with the other works of the City Library.

The fascination for the ‘Liber Floridus’ extends to this day. A new book has recently been published that delves deeper into this magnificent manuscript from the 12th century. In ‘Liber Floridus’, author Albert Derolez has conducted a comprehensive analysis of the entire contents, composition and historical background of the ‘Liber Floridus’.